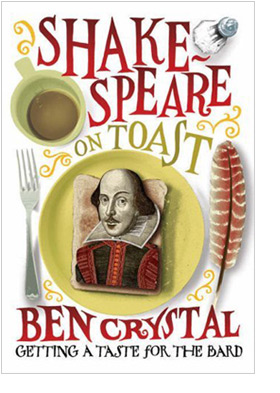

Times Educational Supplement Reviews Toast

The Times; Educational Supplement

‘Who’s afraid of William Shakespeare?’ asks the jacket cover of this little treasure rhetorically and concedes ‘just about everyone’. I remember Dame Helen Mirren claiming that “When you do Shakespeare they think you must be intelligent because they think you understand what you’re saying”, implying that even actors didn’t know what Shakespeare means half the time.

So Ben Crystal, also an actor, sets himself quite a challenge to convince us that Shakespeare is neither elitist nor inaccessible. As I don’t need persuading, I read the book with my sixth formers in mind – many of whom, sad to say, don’t like reading anything, let alone Shakespeare, despite having chosen literature as a specialism.

Shakespeare on Toast is set out like a 5-Act play, beginning with a prologue and ending with the ‘credits’ like ‘Supporting Artists’ and ‘Stage Management’. A nice little touch and one that ensures no chapter is too long, each ‘act’ being divided into ‘scenes’ like a Shakespeare play. Throughout, Crystal’s sense of humour pervades. Opening with the Lear line ‘Never, never, never, never, never’ [A3 Sc5 L306] he proceeds to tell us first what the book is not. Scene 1 made me think it might turn out to be a collection of amusing anecdotes as he tells the tale of Schwarzenegger playing Hamlet! Then Scene 2 reminded me that ‘Shakespeare invented the word assassination’, something I’ve read before, but my students probably haven’t. Likewise, the assertion that ‘if Shakespeare were alive today he’d be writing soaps’.

But very soon I found myself engrossed and actually learning interesting things. More than that, I was beginning to envisage work-sheets, Power Points and role-play activities that could breathe life into the text for students based on what Crystal was sharing.

His writing style is chatty and clear, easy enough for a bright year 8 or 9 to follow and any reasonably competent GCSE student with the desire should have no trouble. However, the book is one that both Literature and Drama students who are anything more than seat-warmers at AS and A-Level ought to read. It will certainly be on my students’ reading list and I’ve already recommended it to the librarian as well as our English Advisor.

So, what is it that makes Shakespeare on toast worth paying for? It is packed with anecdotes, many of which bring at least a smile to the face, all of which are interesting. And there are those bits of fascinating trivia that students should be gathering from somewhere that sometimes prove to be just the nugget you need to add an engaging touch to work. It also has a scattering of apt quotes by writers, producers and actors that are useful and informative.

Nonetheless, that’s what I expected. Act 2 is where the real action starts, with thorough, yet simple to follow explorations of contextual issues surrounding Shakespeare as performed: the stage, costumes, settings characters and language. In each case Crystal’s experience of the theatre and understanding of Shakespeare as a man working in theatre make sense of oddities that often alienate those who assume Shakespeare is too highbrow for them.

As in a real play, act 4 is where the action really hots up. Crystal discusses rhythm. I knew iambic pentameter closely resembles English speech patterns and the ‘de-DUM’ of the iamb is also like our heart-beat. But how well Crystal explains it and then enthuses, ‘What’s even more exciting is that Shakespeare used this very human-sounding poetry to explore what it is to be human.’ Wow – that’s it in a nutshell, just what I’ve spent decades trying to open doors in student minds to!

Act 5 brings it all together in a close analysis of a short section of Macbeth, where Crystal fully explains his theory that Shakespeare wrote his plays in such a way that the actors could quickly and easily work out how he wanted them to say the lines and where they needed to fill in with some acting. And consequently, if we read it correctly, we should be able to follow exactly what he meant, visualise and feel the emotions we’re meant to feel by not only making sense of the words but also using the rhythm.

The structure of a poem is the ‘body language’ that should support the meaning of the content – or makes us doubt it! That’s something I’ve always tried to excite my students about in poetry lessons. Seeing the same thing holding true in the Bard’s plays shouldn’t have come as a revelation, but it’s the detail that Crystal brings to the analysis that gives the ‘AHA!’ moment its momentum.

Even on toast the Bard is absolutely amazing and Ben Crystal is a ‘restaurateur’ par excellance for serving up a seemingly simple smack that actually has enough complexity to delight a gourmet.

He leaves us with a tip worth framing: ‘No matter how complicated, no matter how ostensibly random, how annoying, boring or just plain bad a scene or a line seems to be, there is always a reason for it being there. You just have to find out what it is. And I promise: the search is always worth it.’

Like Juliet I say, ‘Amen to that’

— Edna Hobbs

Comments are closed.