Angel & North Interview

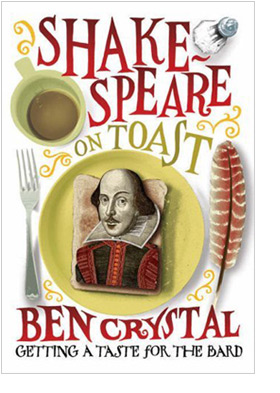

Sitting outside a café just off Old Street, Ben Crystal is interrupted every 30 seconds or so by a panoply of cars revving, motorbikes speeding and trucks beeping deafeningly as they reverse. Nothing, however, seems able to dispel Ben’s jubilant mood. He has a play, One Minute (at the time of writing taking place at N1’s Courtyard Theatre), on the go that he’s both producing and acting in, and a new book, Shakespeare on Toast, coming out.

The latter is his first book to be written solo, following the success of two other tomes on the Bard co-written with his father, David. As it turns out, the press night of his play and the publication of the book clash spectacularly, falling on exactly the same day. One must surely be enough, so is he close to breaking point? “It’s the most exciting thing in the world!” he exclaims to a surprised interviewer. “It’s all kicking off. Sometimes I feel like this is the day I’ve been working towards for the last ten years.”

Our pot of tea arrives. “I’ll be mother,” he quips, falsetto, and takes charge. With his languorous, theatrical body language and intense, grey-eyed gaze, Ben seems every inch the thespian. “I’ve always known that I wanted to be an actor,” he says, “but I knew the jobs would probably be thin on the ground. I’m good with words, so I thought writing or editing would be a good sort of back up career – and when I found this hole on the shelf, the urge to fill it was irresistible.”

His book is, for want of a better word, a Shakespearean manual, without any of the dry drudge that very word suggests. The style is chatty, but still manages to get across the deep love and passion he obviously feels for Shakespeare’s work. “There wasn’t this in-between that made Shakespeare accessible without dumbing him down,” he explains. “The book is about the way to get into Shakespeare through a lot of acting techniques that I’ve learnt – and if you can own these techniques, then you can go to any speech, any scene, any play and own Shakespeare for yourself.”

Some people may find having not one, but two careers on the go – neither of which are known for their stability – a little stressful, so does Ben? “It’s fabulous!” he exclaims again. “I couldn’t sit in an office for the rest of my life. This instability, this not knowing… I love it. It’s exhausting having all these balls in the air, but it’s brilliant too.” But how about the fear if ‘never being employed again’? It seems a shame to dampen his spirits, but isn’t that what all actors complain about? Of course, it doesn’t dampen his spirits at all. “Absolutely, of course there’s that, but I think when you feel that terror, that’s when you are really living.”

So what are the ultimate ambitions of a man as apparently fearless as Ben? This is the question that keeps him silent longest of all. “All I’ve ever wanted was to do good work with good people, who are passionate about what they are doing,” is his answer eventually. “And that’s all I’ve ever done, really. This is perfect. I couldn’t ask for anything more. My book is coming out and I’m going to act in a play that I really care about. Both of these projects are my babies – this is it really, this is the best.” It’s official: his optimistic outlook on life is sickening and you can’t even hate him for it. “I am absolutely sickening,” he agrees, gleefully.

— Emily Paine