The Bookbag Review of Shakespeare on Toast

The Bookbag

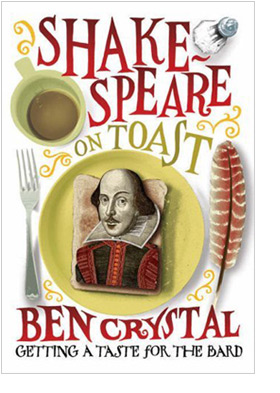

Shakespeare on Toast claims to be for virtually everyone: those that are reading Shakespeare for the first time, occasionally finding him troublesome, think they know him backwards or have never set foot near one of his plays but have always wanted to.

I am not certain where I am located in this classification: I certainly don’t claim to know Shakespeare backwards, but I have certainly set my feet (and more importantly, my ears and eyes) near his plays. I am mercifully unaffected by the pitfalls of the education system’s bardolatry as I went to school in Poland and we only did one Shakespeare play: Macbeth, and it was, of course, read and watched in (excellent) translation.

My main problem with Shakespeare is connected with my problem of reading in English, and in particularly reading poetry in English, which is that anything pre-19th century seems to require so much effort from my brain’s language centres that understanding becomes strained and enjoyment dissolves in that strain. Shakespeare on stage is better – especially if I know the story or if I have the libretto (sorry, the script) handy. So I am in a bit of a dilemma here: I can either enjoy and appreciate Shakespeare in translation, and there are some fantastically brilliant Polish translations of his work, or I can struggle in the original with a hope that it will, eventually, become easier. I guess occasionally finding him troublesome just about covers it, then.

I found Shakespeare on Toast enjoyable and quite illuminating: for a little while at the beginning I was worried, that, despite protestations to the contrary, some dumbing down, if not of the subject himself, then of the audience, will take place; but it was not the case. Crystal divides his book into five chapters (and calls them acts), dealing with progressively more interesting (and arguably more arcane) aspects of Shakespeare.

The first three chapters (sorry, acts) are extremely accessible and deal with mostly basic stuff which many people will be at least vaguely familiar with. Crystal looks at the place of theatre in Elizabethean society, at the way plays were performed, from the physical space to astonishingly expensive costumes and lack of scenery; he presents the fascinating Shakespearean characters and shows – very convincingly – that the themes and stories of his plays are the fundamental stories of humanity, the ones that have been told and retold repeatedly and are still retold now, in EastEnders as much (if not more) as in modern film and theatre. He deals with the ‘Olde English’ issue as well, claiming that 95% of Shakespeare’s vocabulary is perfectly accessible to a modern reader and even providing a very useful list of ‘false friends’.

The last two chapters concentrate on the very core of Shakespeare’s brilliance and importance – and the most powerful argument to why we should at least sometimes watch and read Shakespeare, and not always EastEnders – the poetry, and more specifically, Shakespeare’s revolutionary use and development of iambic pentameter. Sounds boring and dry? It isn’t, or at least it wasn’t for me. Crystal’s enthusiasm makes a surprisingly fascinating task of analysing the meter, counting feet and detecting ends of thoughts. Arcane and forbidding terms become clear and, hugely helped by Crystal’s background as both a linguist and an actor, come to life and start to make sense. He believes that Shakespeare always does things for a reason and, in the final chapter, puts his belief into action in a breathtaking analysis of one highly charged scene from Macbeth.

I doubt whether this book will convince the genuinely bardophobic, despite references to Arnie and rap, but for all those who would like to deepen their limited appreciation, Shakespeare on Toast is an excellent dish indeed.

Highly recommended.

Comments are closed.