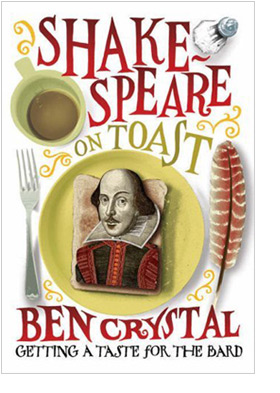

NATE – Review of Shakespeare on Toast

NATE – National Association for the Teaching of English

Ben Crystal will be known to many readers as the co-writer (with his father David Crystal) of Shakespeare’s Words and The Shakespeare Miscellany. In his latest book, he ‘knocks the stuffing from the staid old myth of Shakespeare’ according to the jacket blurb ‘in a breezy, accessible introduction to the greatest writer of plays’. As an actor he has no truck with idea of studying Shakespeare’s drama as anything other than a plays in performance. Obvious, I know, but it still needs repeating.

Ben (I can’t refer to him as Crystal when he’s written such a matey book and would be sure to call me Trev) has enthusiasm, knowledge and his very own style. His enthusiasm comes across in every chapter, imploring the reader – for example – not to be put off by difficult words. There are not that many and he’s counted them. (Mind you 5% of 900,000 is still a lot of words, Ben. I make it 45,000.) In succeeding sections and chapters (cutely called acts and scenes) he describes aspects of Shakespeare that have been perceived as difficult and explains why.

I have a couple of quibbles about that part of his argument. One is that explaining why something is difficult doesn’t stop it being difficult, which was the book seems to imply. Secondly, I felt there was a little too much in the way of ‘Hey this isn’t really hard and anyway look what a cool dude the Bard was!’ (I paraphrase). I’m not sure I would want to plant the idea that Shakespeare isn’t difficult quite so much; it might just make students think about those difficulties once too often.

Ben’s knowledge comes across naturally and without pretension. He brings the understanding of an actor together with the analysis of an academic and it works. The most effective sections, to me, are the two last ‘Acts’ (half the book) where he goes into considerable detail about Shakespeare’s use of metre. There are numerous fascinating examples which bring out facets of Macbeth, for instance, which I had never noticed or taken for granted. This kind of analysis in some writers’ hands could be deadly but here it works really well.

As already hinted, Ben has his own very chummy, colloquial style which will make the book very readable for many people. It can pall a bit sometimes but perhaps I’m not his intended audience. Which is? Certainly most teachers at GCSE and A level (or equivalent) will find it useful. However, I don’t think it’s teachers that Ben is aiming it, but our students. Whether they will find it quite so attractive, I don’t know. Those who are already interested in Shakespeare, yes; those who are a bit iffy about him, perhaps; the rest, who knows? But do buy a few copies and try it out. Shakespeare on Toast may just cut the mustard.

Comments are closed.