Around the Globe Magazine Review of Shakespeare on Toast

Around the Globe Magazine – Autumn 2008

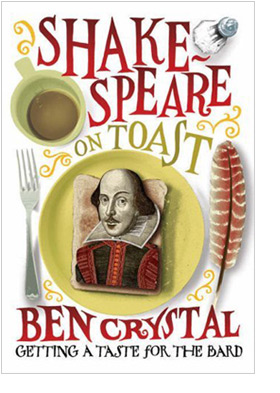

If you’re a reader of Around the Globe, the chances are you’re not too scared of Shakespeare. But there are a lot of unfortunate Bardophobes out there, Ben Crystal tells us, and apparently his book is just the cure they need. At various points in Shakespeare on Toast Crystal reminds us that he used to be one of them – he “once wouldn’t be seen dead near a production of Shakespeare”. But now he’s seen the light, and, well, there’s no zealot like a convert…

And this convert couldn’t be a more enthusiastic advocate for the greatness of Shakespeare, and for the idea that anyone is able to gain access to that greatness if only they know how. So Shakespeare on Toast begins at the beginning, with the basics, and an exhortation that we look at Shakespeare ‘with more of an Elizabethan head on our shoulders’. Crystal examines the experience of watching a play at the first Globe (he has acted at the new Globe himself). He introduces the First Folio and considers Shakespeare’s own reluctance to be published. He extracts character clues from the opening to Hamlet. He describes the relationships of Shakespeare’s stories to the originals they were based on. And then he ventures to tackle the scariest thing of all – all that ghastly, incomprehensible writing!

As the self-appointed scourge of Bardophobia, Crystal seeks to demystify some of the most alarming aspects of Shakespeare (especially as perceived by those who developed their allergy at school): the iambic pentameter, all those difficult olde words, and so on. He shows how a heartbeat keeps iambic time, and uses well-chosen examples from plays and sonnets to teach us to read the metre (as it were).

It’s all very personal – we find plenty of Crystal himself in his book, peppered with first-person references (‘…as my mother would say…’) – and friendly; and it’s full of imaginative and useful analogies. Elvis returning to Memphis; a Beatles cover version by Cher; buying a DVD; a prac-crit of Mos Def lyrics; the instruction manual to an aircraft engine; the birth of Google – and my favourite, the music of Miles Davis (explaining Shakespeare’s jazz variations on the ‘normal’ iambic pentameter theme). The analogies are often silly and often imprecise, but they are pitched perfectly to clarify rather than complicate, and to create satisfying ‘I’d not thought about it like that’ moments.

Crystal is particularly eloquent on what makes Shakespeare’s characters human and remarkable, and it all – of course – comes down to the words. As the book develops, Crystal goes on to expound theories – some old, some new – about how you can read a text, what you can learn from it about the state of the speaking characters and their situations. As an actor, he is keen on the ‘directorial’ clues to be found in the writing, the clues that Shakespeare plants to guide his actors’ movement, gesture, delivery, breathing. By the book’s Fifth Act Crystal is zeroing in on a scene, with the reader now ready to be led through a passage from Macbeth in some detail, pressed to appreciate it through our guide’s closely-read interpretation, and encouraged to apply the same tools to other passages from Shakespeare. Look at the irregularities of metre; look for yous and thous; consider the context in which audiences first saw it. For the Macbeth scene he even plots a graph of line lengths, which sounds (and indeed is) incredibly nerdy, but is actually rather amazing, too.

Shakespeare on Toast is reassuring, and appealing, and Crystal’s bounding enthusiasm is hard to resist. And while there are a few little theories one might contest or little facts that need correcting, these are petty flaws in a valuable book that does what it does very well. If, like Crystal, you’re a bit of a Shakespeare evangelist, you’ll want all your Shakespeare-resistant friends to read it. I’ll certainly be buying copies for mine.

— Daniel Hahn

Comments are closed.